Flatlands

On Unstable Ground

A tension pervades the paintings of Nina Chanel Abney, Mathew Cerletty, Jamian Juliano-Villani, Caitlin Keogh, and Orion Martin. Although they approach their subject matter in very different ways, they share an interest in representing, while upending our understanding of, the phenomenal world. More than simply a categorical style, here representational implies a designation, characterization, or stand-in for reality that intimates a certain falseness. In a society at once fascinated by and suspicious of the concept of “truthiness”—a visceral belief that something is true despite an absence of evidence—it is not surprising that the veracity of representation would be regularly undermined. Underscoring our unease, the artists in Flatlands manipulate their subjects in order to impart their own brands of bizarre unreality. Objects such as Martin’s boot or Cerletty’s vest; bodies, like Abney’s and Keogh’s flattened women; and places—Cerletty’s verdant field, Juliano-Villani’s underwater rock garden—are plucked from life. The departures that these artists make from perceived reality—constructing a figure from traffic cones, revealing the insides of a woman’s torso, suspending a home aquarium’s inhabitants in motionless perfection—key up otherwise innocuous subjects and lay bare their sinister undertones.

The paintings in this exhibition heighten that apprehension by simultaneously seducing and repelling the viewer. Complex compositions, vivid colors, and luscious surfaces, along with subject matter that is curious, sexually charged, or simply beautiful, draw viewers deep into their imaginary worlds. Once there, however, the garishness of those same colors, the dizzying density of the compositions, and the ominous, frightening, or uncanny characters and narratives force us back out, disturbed by what had just intrigued. These competing sensations are at the core of the power of these paintings, allowing them to stay perpetually dynamic and exciting.

The featured artists also share a similar approach to illusionistic space, or depth of field. Their compositions are shallow and sometimes tenuous, as in Abney’s patently flat scenes and Juliano-Villani’s distorted perspectives. They don’t recede deep into an illusionistic distance but stop short, like the scenic flats used to define space on theater and movie sets, conveying a sense of superficiality, even claustrophobia and anxiety. And, like tales performed on stages and screens, the subtle narratives implied by the artists’ invented worlds are often allegorical in nature, their straightforward construction veiling a more complicated intent.

Today, the virtual hyperconnectivity of our daily lives masks a disconnect from the physical world, leading to a yearning for the tactile. Representational art answers this desire to be tethered to reality at a time when the world around us feels so insecure. The paintings in Flatlands also reveal a latent aspect of contemporary American life: the atmosphere of extremes, with fear and unease on one side and ambition, seduction, and luxury on the other. Around the globe, governments, economies, and the environment are becoming increasingly precarious, while forces of instability continue to mount and socioeconomic inequalities accelerate. Conversely, however, aspirations for over-the-top lifestyles show no signs of abating, and social media flaunt an endless parade of flawless self-presentation. The distance these artists create between the real world and their altered verisimilitudes leaves us apprehensive. We recognize ourselves, our longings, and our fears, and yet the mirror these paintings hold up is a funhouse version, warping our familiar comforts into something disturbingly revealing.

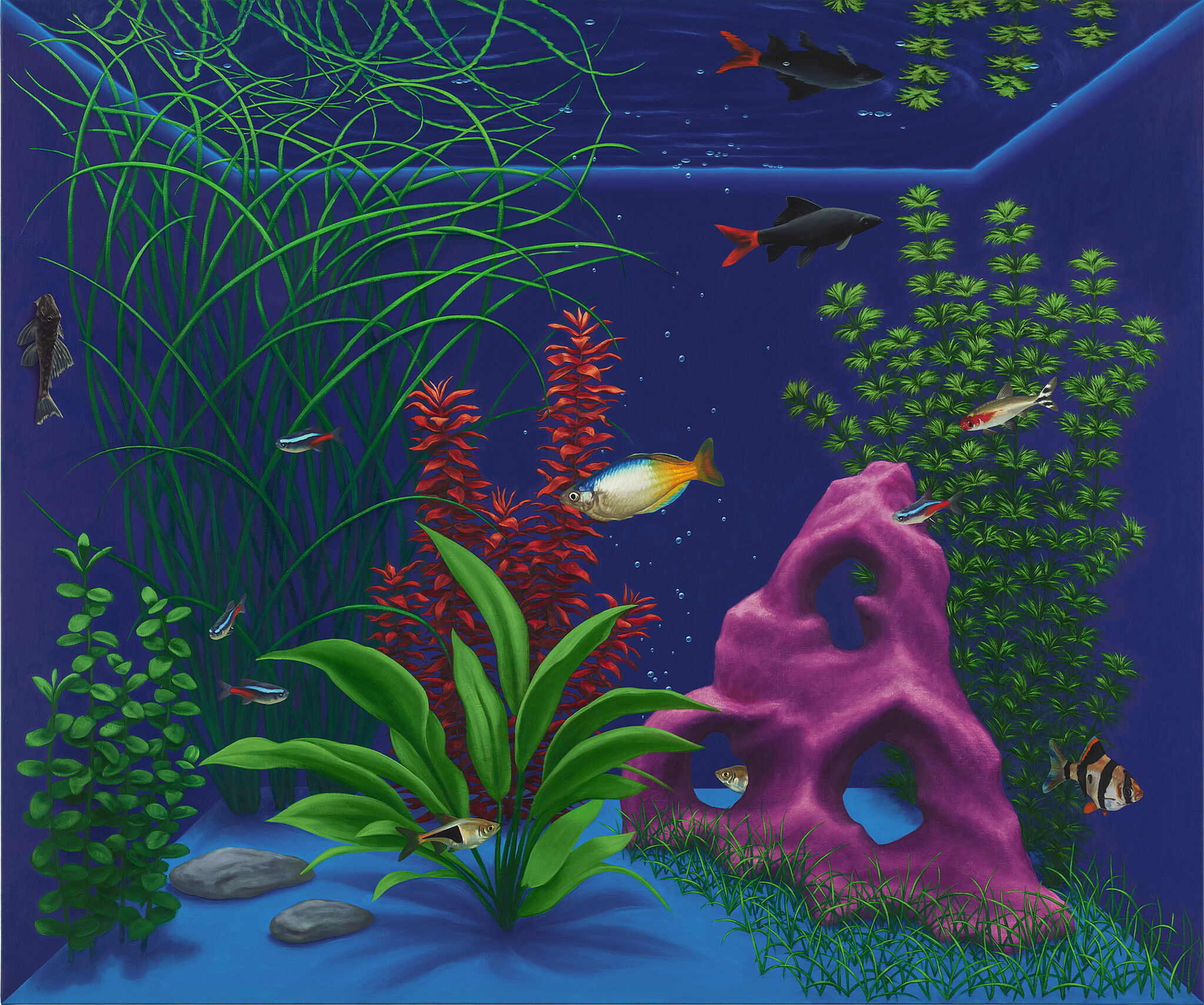

Mathew Cerletty’s unique environments play with the psychology of familiarity and recognition, highlighting the disquiet lurking in the uniform, prosaic, or bland. He has said that having grown up in the down-to-earth suburban Midwest allows him to “find unique territory in the generic.”1 Through intense focus on a banal text (Night of Our Lives; 2014) or the transformation of recognizable objects, like a fish tank (Shelf Life; 2015) or item of clothing (Returns & Exchanges; 2015), into ambiguous and menacing forms, he deviates from convention in otherwise traditional or straightforward scenes. In other works, he merges multiple painting techniques: Almost Done 2 (2015) combines a faithfully illusionistic self-portrait of the artist driving a lawnmower under a painterly cloud with a flat, circular yellow sun hanging over too-smooth blue and green fields indicating sky and grass. These juxtaposed styles complicate any sense of seamless representation, reinforcing the paradoxical nature of his bizarre yet mundane worlds.

Cerletty’s process has always begun with academic painting techniques that have fallen mostly out of favor in recent decades. Alongside his unabashed use of these old-fashioned styles stands his interest in the painstaking, skillful labor of his paintings—approaching the meticulous rendering of hundreds of individual sequins as worthwhile in and of itself, for example. His method challenges contemporary trends, which are characterized by cool, conceptually grounded processes, casually haphazard abstraction, and expressionistic figuration. Cerletty’s early figurative paintings are indebted to John Currin (b. 1962), whose academic portraiture style reveals a preoccupation with class and taste through his perversions of ideals of beauty. In contrast, Cerletty’s fixation on taste manifests not in such exaggerations but in his fastidious process, so earnest it verges on embarrassment due to the time and labor spent, as well as his specifically middlebrow content. His water towers, lawn mowers, J. Crew oxford shirts, and women—lying down, drinking milk, doing yoga—are so banal that his intense focus on them can seem perplexing, but also dryly and darkly humorous. Further accentuating the peculiar nature of these otherwise quotidian subjects, each of Cerletty’s three paintings in Flatlands makes use of a mirroring effect, a technique he frequently employs. This doubling—whether it’s a fish unaware of its twin reflected on the water’s surface above or the perfectly symmetrical sequined pattern on an ornate vest—creates a perception of reality and its doppelganger, with Cerletty’s paintings sitting firmly in the in-between space.

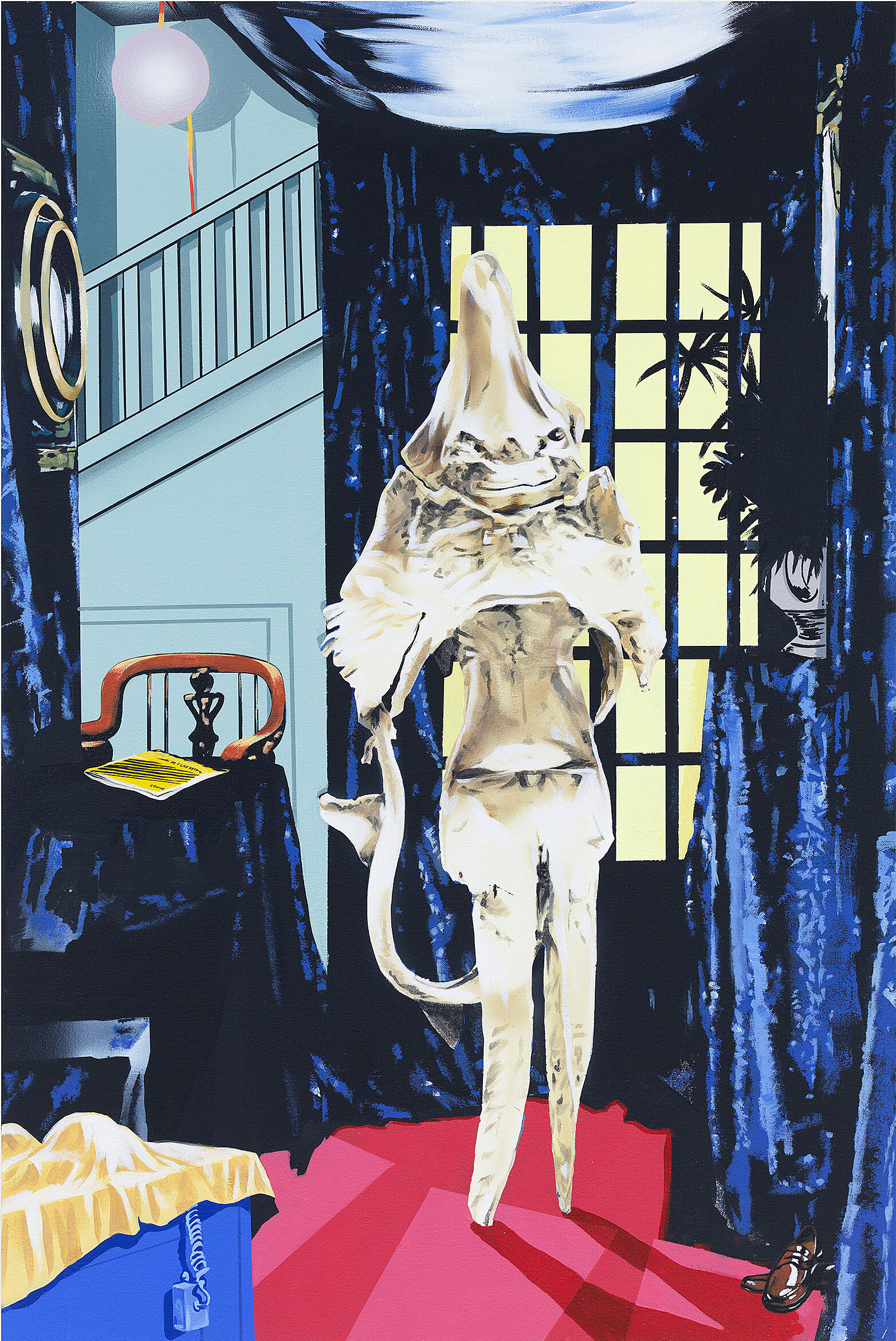

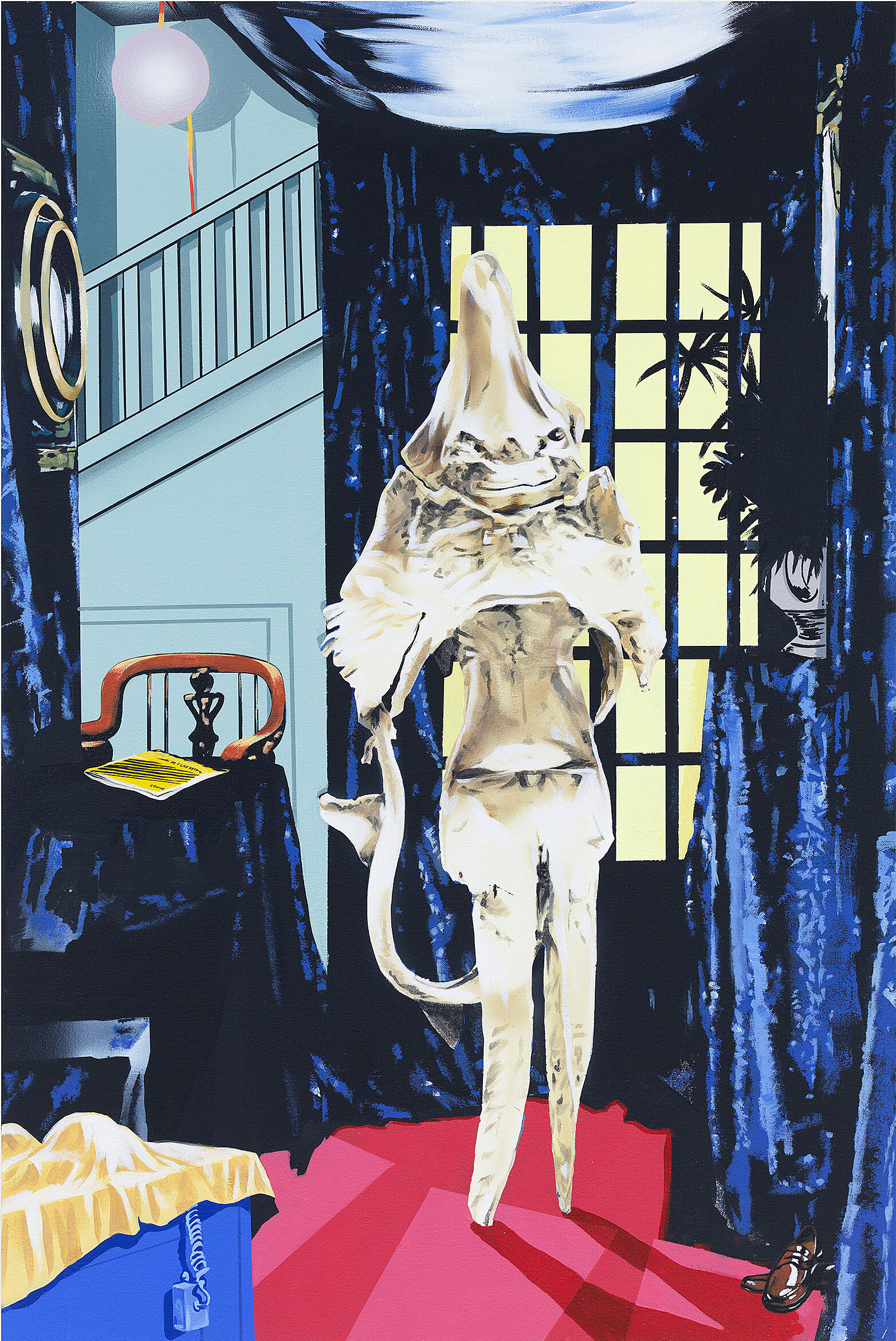

Jamian Juliano-Villani (b. 1987), Haniver Jinx, 2015. Acrylic on canvas, 36 x 24 in. (91.5 x 61 cm). Collection of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; purchased with funds contributed by the Young Collectors Council and additional funds contributed by Stephen J. Javaras and an anonymous donor, 2015. Image courtesy the artist and Tanya Leighton, Berlin; photograph by Gunter Lepowski.

Beyond its confusing duplication of reality, a painting like Shelf Life also challenges the immediate sense of recognition it promises. Though the aquarium of exotic fish and fauna that Cerletty paints is certainly familiar from countless doctor’s offices, restaurants, and classrooms, a close examination reveals an unease specific to the painting. The tank is tightly confined within the canvas’s boundaries, without suggestion of a world beyond its edges; the artist says that he “think[s] of the aquarium's location as the painting itself.”2 Additionally, the finely rendered fish and plants are purportedly alive yet appear still, as if frozen in place. Even the bubbles and ripples of the water seem static, emphasizing the feeling of claustrophobia.

Unlike Cerletty or Orion Martin, both of whose processes are deeply informed by classical technique, Jamian Juliano-Villani’s approach comes from outside of traditional art history. Her reliance on airbrushing—a technique more commonly found on cars, skin, and cardboard signs in store windows than on stretched canvases—connects her work to popular culture and street aesthetics. This association is reinforced by the images that populate her dense paintings. Juliano-Villani voraciously sources imagery, drawing directly from comics, cartoons, technical manuals, and subcultural references. Extracted and crammed into a new context, each rubs up against others culled from altogether different times, places, and sensibilities, such as in To Live and Die in Passaic (2016), where a figure made of an orange peel carries his own segments as he walks across the clear blue water of an aboveground swimming pool. Within one painting, the references can span generations and decades. The resulting scenes incorporate humor, as Cerletty’s do, but on a much faster register. Whereas his humor is dry and slow to reveal itself, Juliano-Villani’s jokes land fast and, like cringeworthy punch lines in a dark comedy, dissolve into discomfort.

Juliano-Villani carefully considers every form she uses, researching cultural references as diverse as Japanese kappa creatures (Haniver Jinx; 2015), forms in an installation by Edward Kienholz (1927–1994) (Boar’s Head, A Gateway, My Pinecone; 2016), and a character from a 1980s public service announcement (To Live and Die in Passaic). Her mashups convey a profound respect for the work of those she is referencing, like the profane animations of Ralph Bakshi (b. 1938) and Wilfred Limonious’s (1949–1999) vivacious illustrations for reggae albums. Many of her pieces germinate from written lists and phrases, quick notations of ideas to seed the beginnings of paintings that explode into the visual overabundance that has become her signature style. This abundance can be seen in Haniver Jinx, where she has placed an apparently smiling Jenny Haniver—a “mermaid” carved and configured from the preserved carcass of a ray fish—in the middle of a bourgeois foyer as if it is a hostess greeting her guests. Beyond the obvious curiosity of the main figure, the scene is filled with other provocative objects: a locked box covered with suggestive lumps, dramatically draped furniture, cartoonish shadows, and a literal fish out of water. Juliano-Villani’s obsessive research and deep understanding of the sources of her subject matter imbue the works with a greater sense of authority than the often crowded compositions, jarring juxtapositions, or frightening forms may immediately imply.

Like Cerletty, Juliano-Villani also looks to fine artists whose work may be currently overlooked by the mainstream art world. Both cite the influence of Patrick Caulfield (1936–2005), a British artist whose Pop-related paintings from the 1970s combine different styles of representation, such as photorealism and illustration, in the same work. Caulfield focused on banalities as emblems of modern life—a concept embraced by Cerletty and Juliano-Villani in their own ways: while the former throws a spotlight on the banal, the latter warps banality until it is nearly unrecognizable. Despite their contrasting approaches, both artists highlight an underlying discomfort with these mundanities of everyday existence.

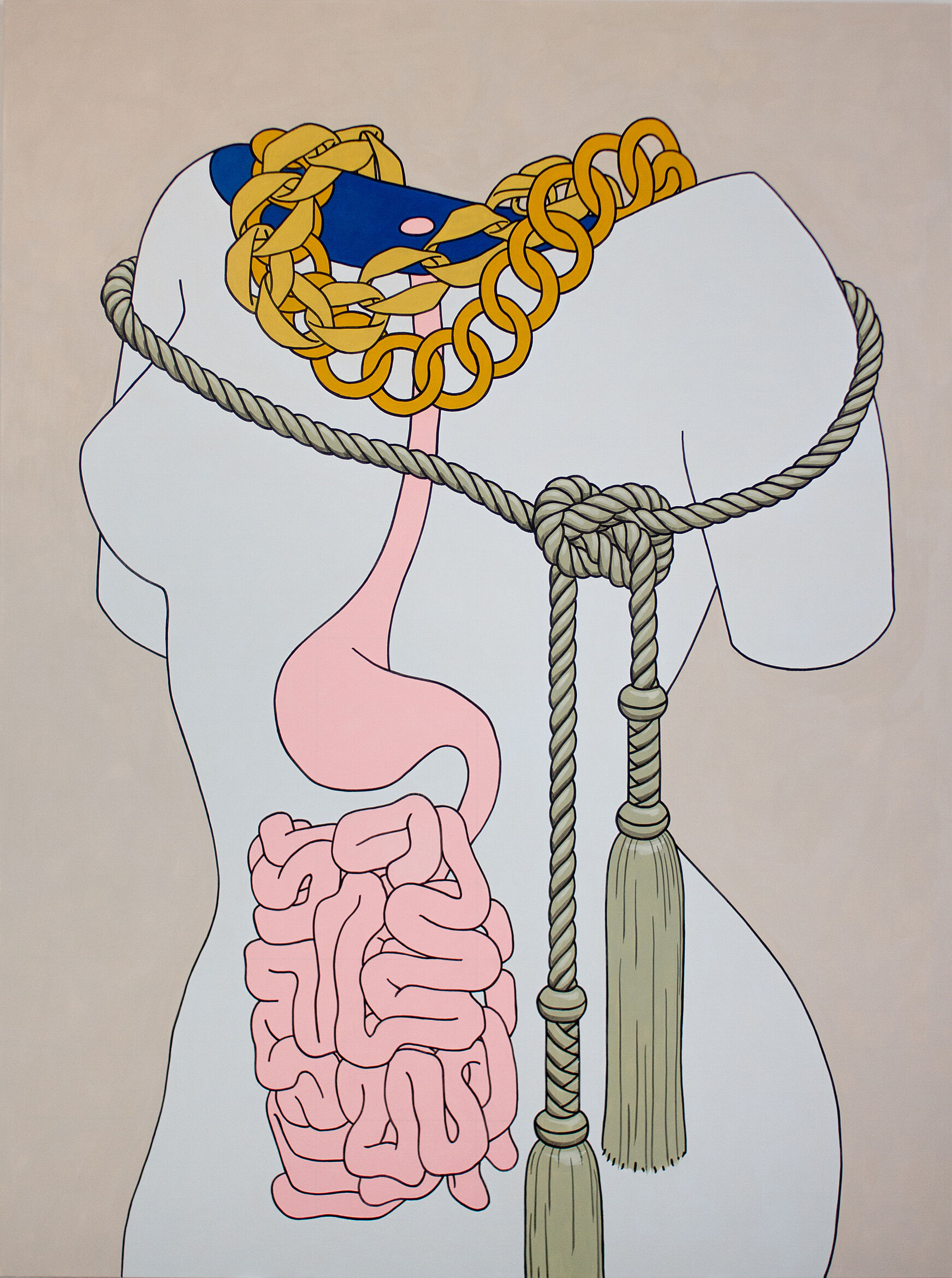

Caitlin Keogh similarly creates a sense of unease with reality in her large, graphic paintings, and, like Juliano-Villani, she blends wide-ranging source material. Rather than keeping their original texture, however, Keogh translates all of her references into her signature style, collapsing them into a new whole. In Intestine and Tassels (2015), for example, she has adorned a mannequin-like female torso with accessories from two very different contexts. Around the nonexistent neck of this headless form, Keogh has draped two necklaces copied straight from the painting Judith with the Head of Holofernes (c. 1530), by Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472–1553), in addition to a decorative rope and tassels based on images she has accumulated over the years. The figure’s pink viscera are drawn in the same simple, economic manner as the necklaces, the torso, and the cord tied around the chest, reflecting Keogh’s interest in depicting “idealized or fictionalized versions of interiority.”3 With a background in technical illustration, she carefully and precisely describes each element of her paintings in clear, clean lines. The artist has said that she strives for an “informational clarity, a kind of explicitness” in the way that her paintings speak.4 Absent of any illusionistic flourishes, color acts as her only addition, distinguishing one form from its neighbor. Keogh collects each of these disparate objects like words strung together to form a sentence; once assembled, however, the grammar often falls apart, allowing for a friction between disjunctive elements.

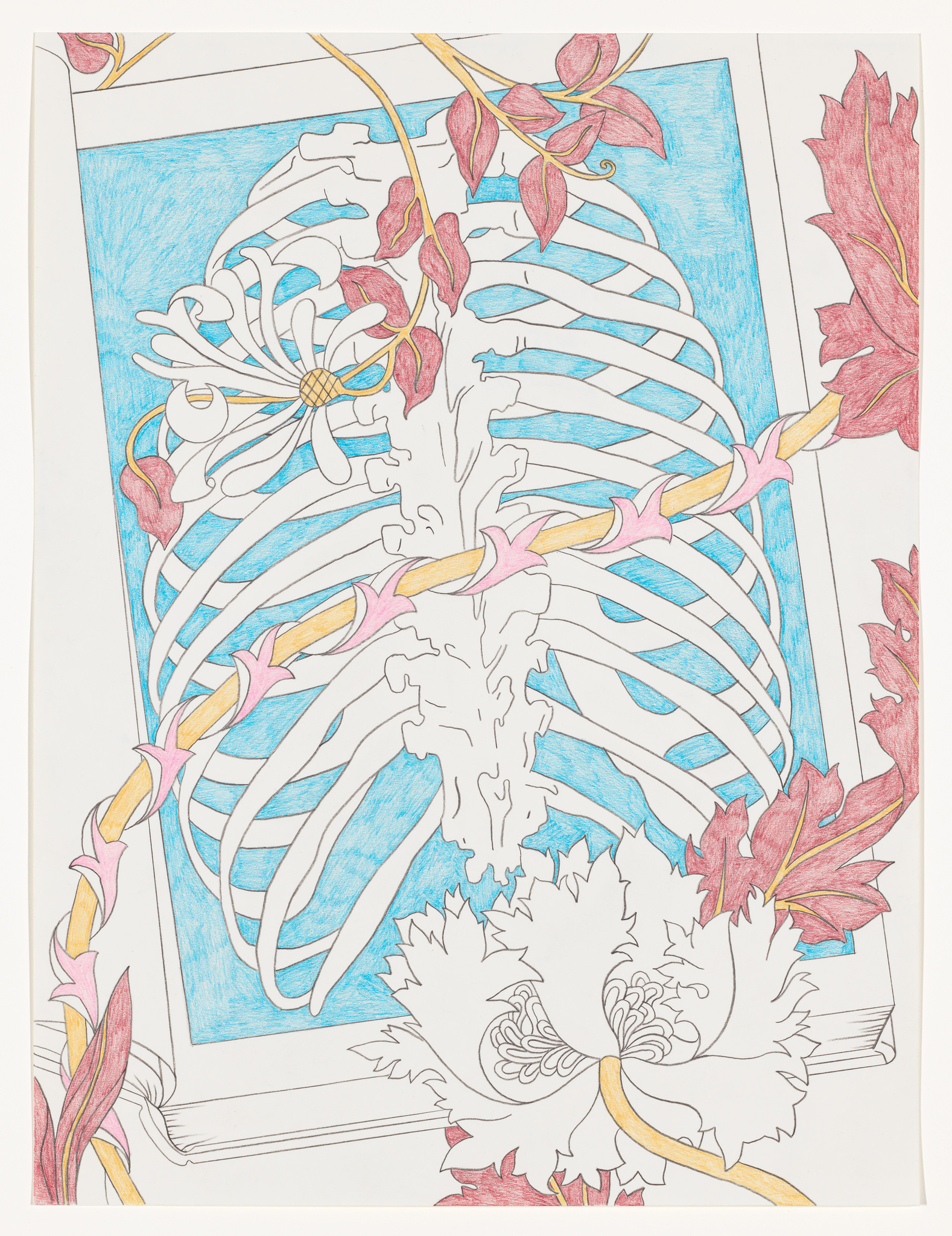

Keogh delves deep into the corners of art history, reinterpreting familiar references, such as the surrealist still lifes of René Magritte (1898–1967) or the adornment of a Mannerist portrait, and reviving otherwise overlooked histories like Christina Ramberg’s (1946–1995) diagrammatic female torsos or the florid canvases of Philip Taaffe (b. 1955) from the 1970s Pattern and Decoration movement. One oft-used source, seen overlaying a drawing of a ribcage in Vines (2015), is the floral patterns of Victorian designer, poet, and socialist activist William Morris (1834–1896), a major inspiration for the Arts and Crafts movement. Morris’s belief that true art, as both a decorative and a functional part of life, must question its connection to moral, social, and political doctrine aligns closely with Keogh’s own philosophy. She incorporates signifiers such as Morris’s patterns, pastel palettes, and simplified figures to express her engagement with ideas of labor, the degradation of the terms beauty and decorative in contemporary art, and the politicized body. All of Keogh’s references are selected to fill her compositions with the weight of their history, shrewdly enriching the work with the politics and positions of these artists from previous generations.

Keogh’s depictions of the female form—headless and idealized, like store mannequins—are simultaneously alluring and powerful yet vulnerable, suggesting the artistic and political battles over the body that she is determined to fight. As in Intestine and Tassels, Keogh often enacts a sanitized trauma on them, punching neat holes through the torsos’ images, putting the visceral insides on display on the outside, or implying a quiet threat with a casually draped rope. In this work, by obliquely pointing to the potently feminist tale of Judith’s decapitation of Holofernes, she takes the suggestion of violence a step further. These dualities are reminders that, despite decades of advancements by feminist artists, the female body continues to be a site for the male gaze, an object to be manipulated into fantasy and stripped of its own agency. Keogh’s women are at once mindless objects and their own forces of beauty and ferocity.

Whereas Keogh deploys limited numbers of streamlined forms to convey complex political ideas, Nina Chanel Abney overloads her canvases with equally simplified shapes, in turn obscuring and revealing the content embedded within them. She works intuitively, almost automatically, with music and books as well as news and images sourced from the internet constantly feeding her information as she paints. Much like Juliano-Villani, Abney parses the cacophony of life into discrete elements. Words found on city streets—checks cashed, ATM, cool, sorry we’re closed—share space with geometric forms and bodies, as visually chaotic as the hurried world around us. In her 2015 painting What, central figures are surrounded by circles, Xs, hearts, and bars that fill and spill out of blocks of color defining the background. The overall effect is of a staccato rhythm that keeps the eye dancing around the canvas, alighting on high notes or getting lost in the noise. Her typically larger-than-life paintings envelop viewers and force a kind of confrontation with the elements of the work.

At times, Abney’s painting takes social justice as its main subject—increasingly so as the news stories filling her studio are more and more politicized. In What and other recent works, police and citizens tussle and face off in aggressive conflicts, the geometries around them exploding to animate the scene. Abney shares Keogh’s interest in the politicized body, both painters simplifying and highlighting the human form to locate moments of manipulation and violence.

With her rudimentary vocabulary of shapes, Abney frustrates easy readings of race and gender roles, combining and confusing expected representations of each character in her scenes. Sometimes she alternates skin tones within a single face, giving a pale face a dark nose or vice versa. In What, two figures—one white, one black—are kneeling at the feet of a police officer, both seemingly in the role of detainee yet both wearing yellow police badges. Here the complications are less about twisting real life into fiction, as in Cerletty’s and Juliano-Villani’s work, and instead present a version of reality that forces us to confront our own unconscious prejudices, without providing answers to the challenging questions these biases pose. Abney’s paintings demand that we engage with their difficult subject matter long after we’ve walked away from her work. As she explains, “I’ve become more interested in mixing disjointed narratives and abstraction, and finding interesting ways to obscure any possible story that can be assumed when viewing my work . . . I want the work to provoke the viewer to come up with their own message, or answer some of their own questions surrounding the different subjects that I touch in my work.”5

All of the artists in Flatlands share an interest in the surface of their works, an attention to the design and finish that is reminiscent of the concerns of pattern or product design. Abney’s surfaces suggest almost no illusionistic depth, resembling collaged paper more than painted canvas. Orion Martin, on the other hand, paints his forms so carefully that the final effect nearly appears computer generated rather than created by hand. If Keogh and Abney reveal the political in the decorative, Martin is interested in the power of the decorative and, like Cerletty, the lure of the unblemished surface.

Like Juliano-Villani and Abney, Martin manipulates otherwise unrelated ideas—sourced from his own inventions, low-resolution images found online, and knickknacks from his studio or home—into a new whole, dreaming up objects and tableaux that have their origin in the world around him but which ultimately result in something quite oddly otherworldly. In Triple Nickel, Tull (2015), for example, he combines two elements, a fanciful high-heeled boot and a theater’s backstage, in a way that is visually and conceptually perplexing. The boot is so finely rendered that each stitch and grommet looks touchably real, yet the form itself has a flatness and weightlessness that contradict that illusion. The stage set, however, is more impressionistically depicted, conveying a dreamlike quality that seems to make it more easily inhabitable by the viewer’s imagination than the bizarre precision of the boot.

Martin intentionally invents scenarios that are difficult to paint; he sets up problems for himself that don’t have real-world, logical solutions. As with the boot in Triple Nickel, Tull, he is often pursuing a hyperreal effect, asking, “How convincing can I make it look?”6 In this, his adversary and tool is light: how it passes through or bounces off surfaces, obscures or highlights them, and reveals their material properties absent the sense of touch. His skillful handling of its manifestation—highlights and shading—gives the boot its tactile realism and the setting its drama and dreaminess. Martin’s uncanny paintings convince the viewer, if only for a moment, that his impossible scenes or creations could exist in the real world, while simultaneously undermining this impression through their patent impossibility. His preoccupation with surface and its tenuous relationship with veracity feels very au courant in a society in which so much is experienced online: despite all the information available for consumption, we are left touching only the smooth glass of the screen.

Like Juliano-Villani and Keogh, Martin shows a strong affinity with the work of the Chicago Imagists of the 1960s and 1970s. While Juliano-Villani’s paintings more closely recall the verbal confusion and violence of the Hairy Who’s aesthetic, and Keogh’s interests lie in the politicalization of the body evident in the work of Ramberg and other Chicago artists, Martin’s paintings synthesize the fantastical realities and slick surface obsessions of painters such as Barbara Rossi (b. 1940) and Jim Nutt (b. 1938). Martin’s combination of recognizable and inert subject matter points away from the scatological references in much of the Chicagoans’ work yet often shares their proclivity toward bodily aggression. Whereas the curves and forms of the boot in Triple Nickel, Tull echo the corsetry of Ramberg’s feminist depictions of undergarments, the tight laces crisscrossing the smooth pink ribbing of its opening verge on anthropomorphism, implying sexual organs and bondage. This insinuation of both seduction and pain, in combination with the darkness behind the theater curtain, signals a sense of enticing dread.

These five artists use the tools and current vernacular available to them to comment on pressing concerns of our zeitgeist. Through their painted illusions of reality, each is shaking the ostensibly stable ground of daily life and revealing it as a false construction. Abney and Keogh engage directly with a revived and necessary urgency around race and gender politics, while Cerletty, Juliano-Villani, and Martin unravel our world in more oblique ways. Yet despite their disparate practices, their works share a common dynamic, simultaneously attracting and repelling the viewer. This taut push and pull of anxiety and desire creates a dialogue with the viewer, as if each painting begins a thought that trails off in an ellipsis, inviting us into the work to complete the thought. Despite this invitation, the challenging and unsettled nature of these works frustrates this exchange and questions our assumptions of representation and reality, leaving us pleasantly disquieted.

1. Mathew Cerletty, correspondence with the authors, December 20, 2015.

2. Cerletty, correspondence with the authors, December 13, 2015.

3. Caitlin Keogh, conversation with the authors, December 17, 2015.

4. Ibid.

5. Huffington Post, “Nina Chanel Abney's Paintings Mix the Pretty, the Political and the Perverse,” February 20, 2012.

6. Orion Martin, conversation with the authors, August 26, 2015.