Remnants and Remembrance

Neopets, The Walking Dead, Clone High, totem pole trench trope, Silence of the Lambs, Picasso’s harlequins, Tilikum, Flowers for Algernon, Lady Train, The Green Ribbon, The Ice Palace. Bunny Rogers (b. 1990) is a collector of cultural artifacts. Often looking to the recent past, she filters an array of quotations from Internet subcommunities, television shows, movies, the news media, art history, and young-adult literature through a distinct formal vocabulary, revealing the emotional potential of both objects and spaces. While Rogers adopts readily available source material, her choice of content is deeply personal. She is, as many of us are, attached to stories and characters from childhood, much of which she spent online:

My family got a computer when I was six or seven. Then they got AOL . . . , so I guess it started with AOL and AOL Kids. . . . I jumped from AOL Kids, Art Forms, to Neopets and was pretty committed to Neopets for the next three or four years. Then I moved on to Furcadia. . . . Then Second Life later on. I just moved from character to character. . . . It was always a component in my life. I guess that’s how I would describe growing up online. Having an outlet I could count on being there."Code is Amoral: An Interview with Bunny Rogers and Nozlee Samadzade,” by Eileen Isagon Skyers, April 2017.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the web-based role-play games that consumed Rogers as a child often encouraged anonymity. Users of these games and contributors to online forums could mask or don any identity they wished. While they—or perhaps, because they—could conceal so much in the way of concrete facts about their lives, they may have felt freer to reveal themselves emotionally. Today, almost two decades later, the perfectly edited images many of us post online create an illusion of sharing and intimacy while actually veiling a separate reality: we are no longer anonymous but have become, arguably, more unknowable.

Rogers’s urgent desire to connect with others, which brought her to these games, is also an ongoing focus of her art.Ibid. In two recent exhibitions, Columbine Library (2014) and Columbine Cafeteria (2016), Rogers wove together meandering narratives using found characters and their pre-existing storylines—namely about social alienation or deviance—and anchored them with details from the media mythology surrounding the Columbine High School massacre of 1999. Rogers, just nine years old at the time of the event, was profoundly affected by the shooting footage that saturated the news media and consumed the public consciousness. Yet, she recalls not consciously grasping the extent of this horror until adulthood: “a small-town tragedy so devastating it swallowed a nation whole . . . resulting in an open question regarding the immeasurable reach of loss—be it individual, collective, communal, or national.”Bunny Rogers, e-mail message to authors, August 14, 2017.

For both exhibitions, Columbine Library and Columbine Cafeteria (in Berlin and New York, respectively), she created sculptural installations based on the specific murder sites within the school, which she embellished with cultural references from her youth in the late 1990s and early 2000s—a period that coincides with the moment when public mourning first began to have an online presence. In researching Columbine’s aftermath as an adult, Rogers became fascinated with the devotee subcultures that had emerged on the Internet around the killers, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold. This controversial “fandom community” of teens and twenty-somethings who fantasize about Harris and Klebold still exists today on personal blogs and Tumblrs, such as The Everlasting Contrast.Sascha Cohen, “The Columbine Shooters, the Girls Who Love Them, and Me.” Vice.com, January 31, 2016.

In her library and cafeteria sculptures, Rogers obliquely probes this taboo obsession, among young women in particular, with the hyper-masculine violence of Columbine. A dichotomy of the seemingly innocent and the sinister converges in Clone State Bookcase (2014), the centerpiece sculpture from Columbine Library.

A near-replica of the high school library’s industrial furniture, this bookshelf is filled with furry stuffed dolls instead of books. Intended to resemble Neopets, Rogers’s highly customized dolls are a reference to her early social-media experiences amassing digital prizes to share and compete with other Neopets gamers.First launched in 1999, Neopets still exists as a virtual role-playing game in which children create and care for computer-simulated pets and connect with other players. Through her meticulous customization of the work and repetition of its elements, Rogers reveals a perverse fixation behind earnest forays into online friendship and fantasy worlds as well as the moral ambiguity of motivations among “Columbiner” devotees: in her words, “You can’t think of Dylan’s death without Eric’s death. I think that’s a fantasy for a lot of people, especially a lot of young people: to remove the fear of being alone in life and in death.”Rogers, e-mail message to authors, August 14, 2017

Rogers herself is motivated by an imagined connection with an “ideal viewer”—one whom she knows does not exist but who somehow knows her source material as thoroughly as she does and “can read the whole out of the sum of many parts.”Bunny Rogers, conversation with authors, June 16, 2017. Because Rogers layers reference on reference, those parts can be difficult to parse. With Clone State Bookcase, Rogers designed the Neopets dolls to be caricatures of the late musician Elliott Smith, a legend for alienated teens whose 2003 death by seemingly self-inflicted stab wounds is still debated.Gillian Orr, “Elliot Smith: Last word on a tormented rock hero,” Independent.com. November 1, 2013. Some dolls wear “Ferdinand the Bull third-place mourning ribbons”—long, black silk prize ribbons embroidered with an image taken from Smith’s tattoo of Ferdinand, an atypically gentle bull of the children’s book. While no individual viewer will be able to unravel all of its densely layered and intricately intertwined significances, Rogers’s work rewards sensitive viewing. It is a conduit between the public and private self, simultaneously inviting moments of access, while refusing clarity. In doing so, it communicates a sense of yearning to find empathy—to locate someone who “sees it and is left with this feeling that they understand: I see you, you see me.”Rogers, e-mail message to authors, August 14, 2017.

By borrowing existing characters, storylines, and objects—albeit ones often obscure or overlooked—with which she once identified, Rogers harnessed the tension between public persona and private emotion as early as her first installation, Sister Unn’s (2011). This work consisted of a website and a vacant flower shop in Forest Hills, Queens, which Rogers filled with bouquets of dyed-black roses left to wilt and dry, preserving just one in a glowing shrinelike refrigerator.Sister-unns.com extended the fantasy of this shop with a somber letter addressed to its “loyal customers” notifying them of the closing. The online “Rose Gallery,” a scrolling aggregation of jpegs of roses, archives website hits like the traces of flowers one might leave on a gravestone when visiting a cemetery. Viewers could only look in from the street, or virtually visit this semiprivate abandoned “house of worship”Louis Doulas, “Artist Profile: Bunny Rogers.” Rhizome. May 15, 2012. to mourn Unn, a fictional character from The Ice Palace, a 1963 Norwegian young-adult novel.The Ice Palace (ls-Slottet, 1963; English translation, 1966) by Tarjei Vesaas is a Norwegian novel about a friendship between eleven-year-old girls that ends tragically. Unn is a social outcast who, befriended by a more popular girl, experiences social companionship for the first time. After alluding to queer desires for her new friend, Unn does not want to face Siss and skips school to visit an “ice castle” created by a waterfall in the woods, where she dies from hypothermia. While paying tribute to a literary figure that few American viewers would recognize and by only permitting online access, Rogers calls for sympathy through this elegiac work’s tropes of mourning: an altar piece, flowers, ribbons, and abundant black.

A preoccupation with mourning and its physical manifestations runs throughout Rogers’s practice. In the exhibition Columbine Cafeteria, chapel-like stained-glass windows rendered her school cafeteria mise-en-scène into a site of ceremonial remembrance, which Rogers then filled with sculptures that serve as metaphorical reliquaries. Mandy Memorial and Mandy Mop (2016), a heap of industrial garbage bags and cans, flickering battery-operated candles, and empty wine bottles all dusted with fake snow, resembled the aftermath of a party as much as it did a provisional vigil.

As with much of Rogers’s work, the constituent elements of Mandy Memorial appear mass-produced yet are highly customized or finely wrought versions of common objects. The level of detail with which she imbues these objects might seem to fetishize the violence. Instead, her work contributes to a conversation begun by works such as Mike Kelley’s thirty-two-chapter multimedia installation Day is Done (2005), which re-created high-school yearbook photos of extracurricular activities, and Sue De Beer’s Hans und Grete (2002), a video installation that referenced popular horror films as well as the Columbine massacre. Both installations reflect on the ways in which trauma and loss are processed, particularly by teenagers. Rogers builds on the groundwork laid by these artists, bringing to the subject the viewpoint of her generation, one that saw Columbine so pervasively displayed and slickly packaged by the media and was therefore drawn to early online platforms that highlighted the messiness of individual subjectivity.

Whether votive candles, wilting bouquets, or ribbons tied to any available object, Rogers’s symbols of mourning almost all draw from the vernacular of, temporary memorials. Such memorials—impromptu accumulations built on roadsides and at sites of mass tragedy—are markedly different from public memorials valorizing “great men” of history or war veterans. While spontaneous memorials are not a new phenomenon, public-facing responses to grief have been on the rise in the United States.Erika Doss, Memorial Mania: Public Feeling in America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), 71. As art and cultural historian Erika Doss explains: “The material culture of grief . . . embodies the faith that Americans place in things to negotiate complex moments and events, such as traumatic death. . . . These things are central to contemporary public recollections of loss and performances of grief not only because they are inexpensive and easily available but because they resonate with belief in the symbolic and emotional power of material culture.”Ibid. The “performances of grief” in Rogers’s work—such as reimagining floor mops as bodies holding tears rather than implements for absorbing water—and the attention she pays to even the most seemingly minor details, from hand-dying the mop fibers to discreetly affixing customized tags, demonstrate her commitment to the possibility of objects not only acting as vessels for grief, but also affecting direct change on the mourning process.

The power of material things and spaces to contain complex emotions and impress those feelings on the viewer is central to the experience of Bunny Rogers: Brig Und Ladder, the artist’s first solo museum exhibition in the United States. Rogers designed the show in two parts. The first is a tableau subtly echoing the Columbine High School auditorium, in which an animated video takes the place of a stage. The second, accessed through a curtained doorway, is a “backstage” room, populated by spotlit objects in sets of three. Moving beyond the primary massacre sites of her previous Columbine exhibitions to a place in the school where students hid and later returned to retrieve belongings they had left behind, here Rogers explores a space of tentative refuge or sanctuary after a crisis, more evocative than exactingly replicated. The video’s haunting emptiness reinforces the gallery’s minimal furnishings: plush theater seats, red wine–colored curtain, mauve carpet, and an oversized body-pillow sculpture in the likeness of Tilikum, the killer orca whale.Tilikum body pillow (2017) is based on the SeaWorld orca who killed three people during captivity. This austerity transports the viewer not to Columbine, but into Rogers’s fantasy representation of Columbine, blurred with other memories and cultural associations in an imagined memorial tribute to family and failed relationships.

This tribute, in contrast to the seemingly improvised Mandy Memorial, occurs in a theater—a location that announces to the viewer that this is, indeed, a performance. The “act” of mourning literally takes the stage in the projected video, A Very Special Holiday Performance in Columbine Auditorium (2017), in which Rogers buries her true identity within layered personages. Three cartoon teen girls perform “Memory” from Cats (1981) as if taking part in a school recital. Rogers’s own voice emanates from the animated singer, who is rendered with the artist’s signature long hair, in this Russian cover of the melancholy song—an acknowledgment of her family’s heritage. “Memory” is the iconic song of the lonely Grizabella, the Glamour Cat, who reminisces about the great beauty she once was. Unwelcome among the tribe of younger, sprightlier Jellical Cats, Grizabella is one of many of the archetypical outcasts found throughout Rogers’s work. In A Very Special Holiday Performance, Grizabella herself never actually appears. One hears only her familiar melody and sees, in her place, a sullen cartoon teenager, whom few will recognize as Joan of Arc reimagined by the creators of MTV’s dystopic Clone High (2002–3). Another avatar for Rogers, Joan is a misanthrope in this obscure, fictional high school filled with animated versions of famous figures from history.

Although Rogers alludes to the presence of autobiographical details in A Very Special Holiday Performance in Columbine Auditorium, the personal is illegible through the layers of fiction. Beyond simply suggesting that the self is a series of performances, Rogers again demonstrates an ability to publicly reveal intimate emotions while keeping the narrative specifics veiled and therefore private. The cartoon Joan is an ongoing stand-in for Rogers. In an earlier video, Poetry reading with clone of Jeanne d’Arc (Joan of Arc) in Columbine Library (2014), Rogers recites her own poetry while occupying Joan’s cartoon body. Touching on alcohol abuse, physical assault, and heartbreak, these first-person poems are spoken with juvenile urgency but are devoid of context, preventing the viewer from evaluating their veracity. Rogers’s somber delivery evokes a burial prayer or a student reading aloud in class—one of the only situations, she has said, in which she felt able to speak as herself growing up.Rogers, conversation with the authors, June 16, 2017.

Rituals of mourning, such as dedicating a song to honor the deceased, similarly offer the mourner comfort in distance but also community. Community is central to Brig und Ladder. In A Very Special Holiday Performance in Columbine Auditorium, Rogers as Grizabella as Joan of Arc singing “Memory” is joined by two avatars representing loved ones: a duplicate Joan with short hair for her mother and another Clone High character.This other character is an unnamed character voiced by Mandy Moore who appeared in one special episode of the show.

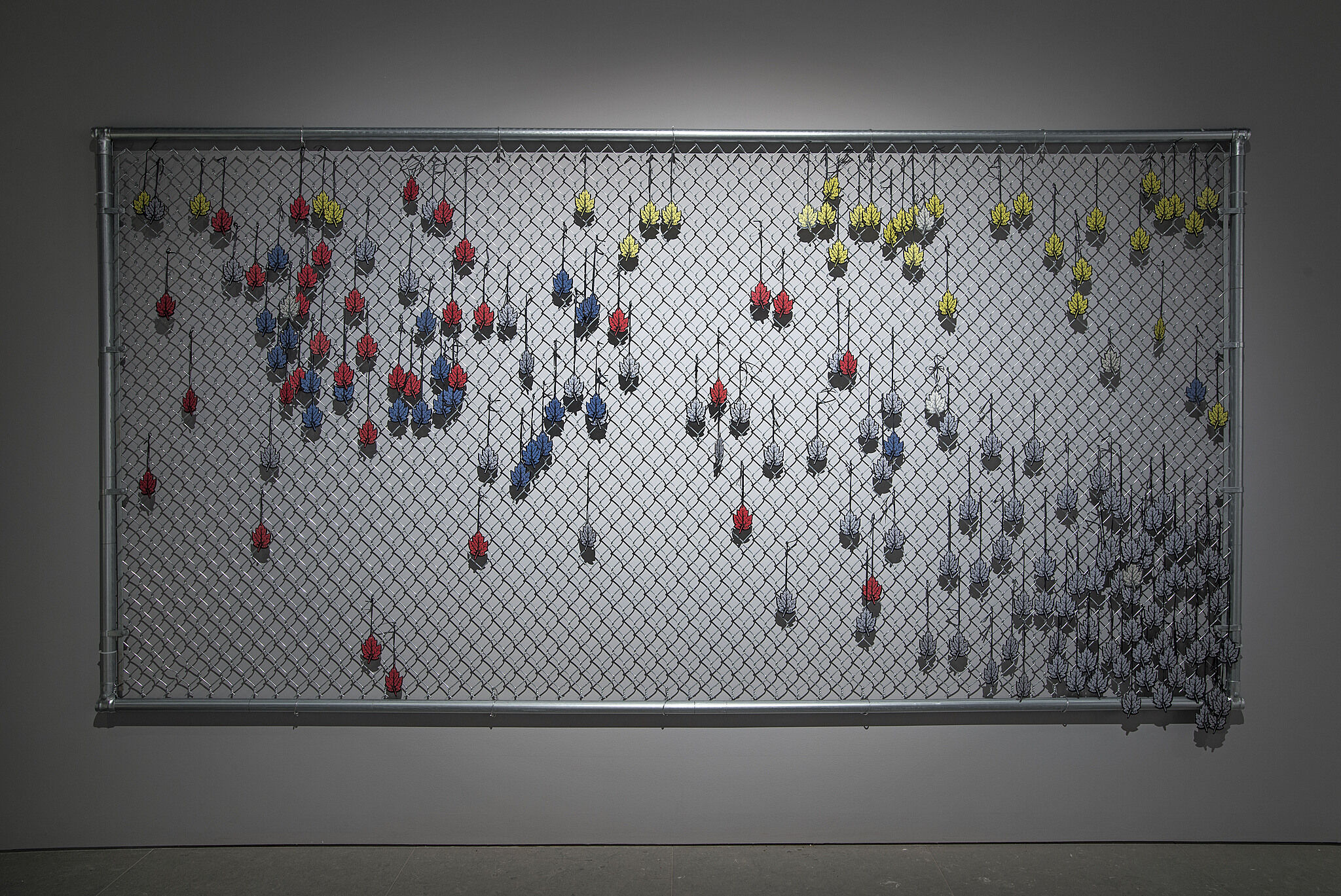

In the back gallery, discrete sculptures—ladders, mops, and chairs—appear in triplicate but the room emanates a sense of emptiness; it serves as a memorial to a love triangle that destabilized Rogers’s senses of both self and community. None of these objects are useable by design and, for Rogers, they therefore act as metaphors for absence and loss. Her ladders with missing rungs, for example, are a physical manifestation of the idea of “losing one’s footing” whereas her chairs are “wounded” with bullet holes, externalizing the private pain of dissolved relationships.Bunny Rogers, conversation with the authors, January 24, 2017. Here Rogers has pulled back the curtain on her Columbine-Clone High world to expose its staging, hinting at the revelation of something “real.” But her curtained doorway leads only to a space that is even more obliquely metaphorical, where Columbine starts to fade away. What remains are merely remnants of her Columbine references, such as the chairs. One sculpture in this space is Memorial Fence (2017), a chain-link fence hung on the wall and decorated with what appear to be car air fresheners in the shape of leaves.

A structure that often divides public from private property, the fence is a reminder of the porous barrier between the internal and exterior selves. Rogers often works with industrial fabricators and commercial-grade materials as well as with a network of friends and Instagram followers, who for this show painstakingly hand-painted the three ladder sculptures with metallic Sakura Gelly Roll pens, a material that holds personal significance for Rogers.Rogers’s hybrid production—employing both the hand made and the outsourced—also serves to almost humorously subvert the hypermasculinity of industrial art production more commonly associated with male artists. For example, her ladders, with their simple geometries and repetition of forms, recall Donald Judd’s “stack” sculptures such as Untitled (1965), which the artist painted himself using a limited-run laquer paint made by the Harley-Davidson Motorcycle Company. Her methods of production reinforce the dichotomy between intimacy and distance. Yet, the degrees of removal Rogers places between herself and her public representation, whether abstract or figurative, make her seem markedly inaccessible to viewers. She distances them and isolates herself, but paradoxically elicits empathy in the process by effectively reproducing for viewers the state of aloneness her work takes as subject. While Brig Und Ladder likely culminates Rogers’s engagement with the Columbine narrative framework, the exhibition does not offer a conclusion; instead it takes us down yet another rabbit hole in its recognition that bereavement is unending. Taken together the three “chapters” of the series echo the mourning process. If, as Rogers has explained in simplified terms, Columbine Library was about the pain of being alone and experiencing loss, and Columbine Cafeteria was about the solace of finding community in coping with tragedy, Brig Und Ladder is about the subsequent loss of that companionship, reigniting a perpetual cycle in which intimate relationships have the capacity to heal, but also to create new wounds.Rogers, conversation with the authors, January 24, 2017

How one reveals pain to others, how people create a sense of community around painful loss by sharing in collective mourning, and how forms of media—from the 24-hour news cycle to turn-of-the-millennium cartoons to the Internet—can shape empathy for both victims and perpetrators, are at the heart of Rogers’s engagement with the Columbine shooting. Her work suggests that Columbine was relatable for her generation, not simply because the perpetrators and victims were essentially their peers at the time, but perhaps, in part, because they could participate in a narrative that formed not only locally through temporary memorials but also more widely through an online community. By expressing sorrow, horror, and fascniation on a media platform that invites connectivity between strangers and content, individuals could, in theory, project themselves into this public tragedy. For those like Rogers, who grew up with the Internet, the Facebook profile of a deceased friend or loved one can feel like the most intimate place for a memorial.“Code is Amoral" Although Rogers has said she would find growing up with today’s Internet to be overwhelming, her work highlights the possibility of finding pockets of sincere emotion and authentic connection in a highly mediated social world.Rogers, conversation with the authors, January 24, 2017. Her work reminds us that mourning is another performance, always mediated for the public, but nonetheless intensely personal.

Rogers’s tenderly rendered sculptures materialize the otherwise immaterial or highlight the otherwise overlooked. This duality reflects the contemporary attitude toward temporary memorials, which are now obsessively collected and preserved in museums and civic archives who categorize and inter what was once ephemeral. As Doss argues, “This segues with contemporary assumptions that everything—every bit of information—is valuable and must be saved. This, in turn, helps direct the contemporary historical archive and the stewardship of history toward the terms of personal experience and public feeling.”Doss, Memorial Mania, 73. Throughout her work over the past decade, Rogers has consistently expressed a longing for personal immediacy and community attachments. Her strategy of embedding her own experience, or what appears to be so, into fictional narratives—whether through voiceovers, dedications, or her use of materials that carry personal significance—guards emotional trauma and amusing memories alike. Occupying other subjectivities, and establishing bridges of connection with the viewer through alienation and distance, Rogers generates a space for empathy. At a moment when online privacy and anonymity have given way to viral memes and spurious news stories, and when these conditions of communication and connection make the possibility of really knowing an individual ever more elusive, Rogers’s enigmatic work speaks to us with remarkable insight. Her personal cosmology carries a private subtext but links her story to a broader, increasingly shared network of public memory and perpetual audience.