Alan Michelson: Site Readings

A group of red wolves stands atop a small hill. They appear alert and at ease, surveying their surroundings, periodically sitting, lying down, or wandering off. Yet a sense of disquiet pervades Alan Michelson’s video Wolf Nation (2018). A warm purple tint obscures the environs, although intermittent falling leaves provide a clue to the time of year. Instead of forest sounds, the viewer hears a haunting, howling score composed by White Mountain Apache artist Laura Ortman, and the wolves move and react independently from this enveloping audioscape.

Michelson made Wolf Nation using webcam video from a wolf sanctuary in New York State, transforming the pixelated footage into an elegiac contemplation of displacement and survival. The red wolves, a species native to what is now the southeastern United States, belong to one of the world’s most critically endangered species, with current estimates suggesting a wild population of approximately twenty.See “What Is the Legal Status of the Red Wolf?” on the Wolf Conservation Center official website.Michelson links their precarious survival to the colonial dispossession of the Munsees, the Wolf Clan of the Lenape people, whose homelands include the site of the sanctuary. This cross-species connection resonates with Haudenosaunee theology, which proposes that the “interconnectedness of all life is sacred and key to human freedom and survival.”Jolene Rickard, “Visualizing Sovereignty in the Time of Biometric Sensors,” South Atlantic Quarterly 110, no. 2 (Spring 2011): 469. In this formulation, Rickard is paraphrasing the presentations of Sotsisowah (John Mohawk), author of A Basic Call to Consciousness, who played a pivotal role in the preparation and presentation of Haudenosaunee papers at the United Nations conference in Geneva in 1977.An equitable, relational approach to the land is at the crux of Wolf Nation, the centerpiece of Michelson’s exhibition at the Whitney Museum, and it recurs throughout the artist’s decades-long practice. Michelson is a Kanyen’keha:ka (Mohawk) member of Six Nations of the Grand River, which has representatives from all six nations of the Haudenosaunee. He foregrounds Indigenous knowledge systems in his work, drawing attention to the interconnected ecological and social histories of place.

Wolf Nation’s purple-and-white pixelated palette and elongated horizontal format centers Haudenosaunee culture through its relationship to the wampum belt. These belts, often used as tools of diplomacy, feature intricately beaded purple-and-white patterns that narrate history, traditions, and laws.The following excerpt, shared with me by Alan Michelson, provides further context on the role of wampum belts in political diplomacy: “The five open hexagons represent the Five Nations. The three white wampum lines at the ends of the belt represent the three warnings that were always given a hostile or an enemy nation to cease warfare and obey the laws of The Great Peace. After the third warning had been ignored, the combined Iroquois attacked the enemy people but only after they had given three chances to change their minds or hearts. If a War Belt was returned by a nation with a string of white wampum, it meant that the nation who had sent the belt back did not want to take part.” Tehanetorens, Wampum Belts of the Iroquois (Summertown, TN: Book Publishing Company, 1999), 52.The video’s visible pixels replace the Quahog-shell beads typically used in the belts, and the purple coloration indicates a message of great urgency, communicating in this case the dire situation of the wolves.“Wampum,” Haudenosaunee Confederacy official website. Accessed October 11, 2019.As a kind of digital wampum belt, the work affirms Indigenous visual sovereignty, which Tuscarora artist and scholar Jolene Rickard argues is inextricable from Indigenous legal-political sovereignty, a multifaceted concept encompassing the self-maintenance of communities, lands, and cultures. Michelson’s use of traditional subject matter reflects an important aspect of Rickard’s articulation of these concepts: “Tradition as resistance has served Indigenous people well as a response to contact and as a reworking of colonial narratives of the Americas,” she writes. “Artfully deployed within Indigenous communities, traditions are a reinvestment in a shared ancient imaginary of self and a distancing strategy from the West.”Rickard, “Visualizing Sovereignty,” 472.In citing the wampum belt, Wolf Nation affirms the sociopolitical system in which it is used.

The footage in Wolf Nation comes from the Wolf Conservation Center, a sanctuary in New York State where the species is sustained through a captive breeding program. Protecting the wolves from loss of habitat, hunting, and other existential threats, the sanctuary has overseen the return of various wolf species to their original habitats, and it spearheads critical education and advocacy on their behalf. Although the organization undertakes essential work to restore the wolves to their wild homes, those that we see in Wolf Nation are in a monitored enclosure. Such paradoxes resonate throughout Michelson’s work: in order to survive, the wolves are held in captivity by the very system that has left them on the brink of extinction.

The conditions arranged to protect the red wolves—life on a designated preserve distinct from surrounding territory—have roots in the nationalist nineteenth-century American imagination. Artists, intellectuals, and politicians of the period sought to develop an identity distinct from Britain’s cultural hegemony.This reductive imagining of the land as wondrous and uninhabited has been firmly established by art-historical scholarship on the Hudson River School. The introduction to American Paradise: The World of the Hudson River School, the catalogue for a 1987 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, begins, “Since the discovery of the North American continent and the beginning of the difficult process of its occupation and settlement by pioneers, the physical and mental possession of the land has been the focus of attention for Americans of whatever stripe. . . . Work and wonder were common companions in such an exploratory situation, but fear and dread of the landscape came to be replaced by loving awe.” Kevin J. Avery et al., American Paradise: The World of the Hudson River School (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987), xvii.To do so, they turned their attention to the land, glorifying imaginings of its “wild, romantic, and awful scenery.”This appears in an 1816 address from future New York Governor DeWitt Clinton: “Can there be a country in the world better calculated than ours to exercise and exalt the imagination—to call into activity the creative powers of the mind, and to afford just views of the beautiful, the wonderful, and the sublime? Here Nature has conducted her operations on a magnificent scale: extensive and elevated mountains—lakes of oceanic size—rivers of prodigious magnitude—cataracts unequaled for volume of water—and boundless forests filled with wild beasts and savage men, and covered with towering oak and the aspiring pine. This wild, romantic, and awful scenery is calculated to produce a correspondent impression in the imagination." Quoted in Oswaldo Rodriguez Roque, “The Exaltation of American Landscape Painting,” in American Paradise, 22.The grandiose paintings of the Hudson River School, a recurring reference in Michelson’s work, were one crucial expression of this impulse. Inspired by this artistic movement and others (and acting in response to the rapid industrialization of cities), politicians and philanthropists began to push for the creation of national parks, further displacing already-uprooted Indigenous inhabitants and criminalizing their use of the land.Karl Jacoby, Crimes against Nature: Squatters, Poachers, Thieves, and the Hidden History of American Conservation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014).This rigid bifurcation between unprotected land (exploited for commercial purposes) and protected land (unused and uninhabited by human beings) continues to shape the modern mainstream conservation movement, even as it disregards the rights and sovereignty of Indigenous communities.This subject forms part of a global conversation about Indigenous sovereignty and oversight over protected lands. Mainstream conservation frequently treats the Indigenous inhabitants of sites whose ancestral homes overlap with vital biomes under protection as obstacles to be removed rather than essential stakeholders who are best equipped to manage and protect their lands. See Alexander Zaitchik, “How Conservation Became Colonialism,” Foreign Policy, July 16, 2018.The relational approach of Wolf Nation draws on a powerful model of harmonious land use, echoing Haudenosaunee governance frameworks that propose that it is “the renewable quality of the earth’s ecosystems that sustain life.”Rickard, “Visualizing Sovereignty,” 469.

Michelson, who trained as a painter, at times refers to the Hudson River School in his work, particularly in the video Shattemuc (2009), which reveals the stark present-day conditions of sites those painters so gloriously depicted. Shattemuc is titled after an Indigenous name for the Hudson River. One spring evening in 2009, the artist sailed upriver from Hook Mountain to Haverstraw, New York, on a former police boat equipped with a powerful marine searchlight. His camera mounted on a tripod, he filmed the light beam as it scanned and illuminated the shoreline. The resulting work subverts the tradition of Hudson River School landscape paintings. Instead of their godlike, totalizing perspective, one sees only what is actively illuminated. Instead of an uninhabited landscape (or one occasionally inhabited by fictive colonial stereotypes of Indigenous subjects),Jolene Rickard argues that there is a historic relationship between landscape art and Indigenous peoples, and that landscape art played a role in “constructing Indigenous land as an American possession while reinforcing the desired erasure of Indigenous peoples.” See Rickard, “Aesthetics, Violence, and Indigeneity,” in “Indigenous Art,” Public 54 (Winter 2016): 60.the searchlight reveals housing developments, transit infrastructure, power lines, roadway lighting, and a quarry where stone is crushed and extracted and asphalt is produced. Instead of an awe-inspiring, majestic landscape, Michelson presents one implicated in the lifestyle and operational detail of extractive consumption.

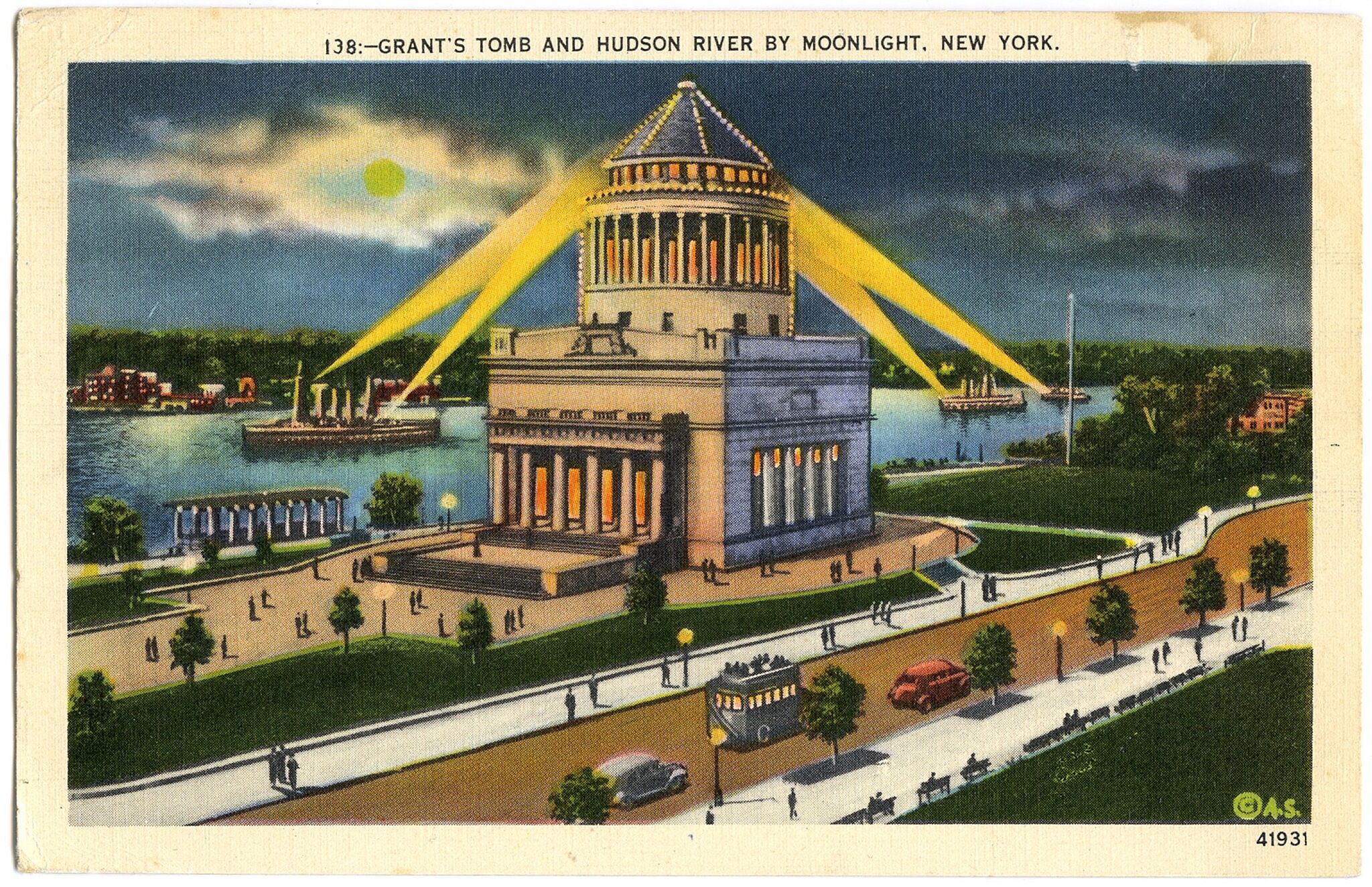

Shattemuc references other popular nineteenth-century visual and cultural forms such as moving panoramas—long, scrolling, continuous landscape paintings—and Hudson River Night Line steamboats, which shone bright spotlights onto monuments for their passengers’ entertainment. Contrary to the monuments glimpsed in those paintings or illuminated on those cruises, Michelson presents “a slow, ponderous contemplation of the ordinary” as he traces the shoreline’s transition from forest to suburban housing developments surrounded by cars and artificial lights.Kate Morris, “‘Rising into Ruin’: Alan Michelson, Robert Smithson, and the (Post) Modern Landscape,” in the online addenda to Visual Culture of the Ancient Americas: Contemporary Perspectives, ed. Andrew Finegold and Ellen Hoobler (New York: Columbia University Department of Art History and Archaeology, 2017), 16.But, as art historian Kate Morris astutely observes, “In Michelson’s hands, banality is powerful: the panoramas of ruin we confront in . . . Shattemuc are devastating precisely because of their ubiquity; these are scenes we know to be repeated in environments throughout the world.”Ibid.Shattemuc extends the investigations of artists such as Ed Ruscha and Robert Smithson who examined the built environment of capitalism and the industrial monuments of urban sprawl. It evokes, for example, Ruscha’s Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966), a twenty-five-foot panorama-like artist’s book depicting all the buildings of the famous mile-and-a-half section of Sunset Boulevard. At the same time, the spotlighting strategy of Shattemuc disrupts the “controlled darkness” that rendered nineteenth-century panoramas effective by eliminating extraneous objects whose sight would disrupt the sense of illusion.Noam M. Elcott, Artificial Darkness: An Obscure History of Modern Art and Media (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 49.Eschewing the artificial darkness of those panoramas—which would become a cinematic dispositive—he cuts through the actual darkness of the night with his spotlight. Its beam is often dulled or washed out by the electric lights ashore, conveying the futility of attempting any totalizing, singular perspective.

In each of his works, Michelson considers the layered and suppressed histories of place, selecting his sites and subject matter based on rigorous research. The stretch of water traversed in Shattemuc, for example, saw a violent encounter in 1609 between Henry Hudson’s crew and a local Indigenous group during Hudson’s return sail downriver toward the island of Manna-hata, subsequently renamed Manhattan by its colonizers.This relevant passage from Robert Juet’s journal of Hudson’s 1609 voyage reads, “Then came one of the Sauages that swamme away from vs at our going vp the Riuer with many others, thinking to betray vs. But wee perceiued their intent, and suffered none of them to enter our ship, Whereupon two Canoes full of men, with their Bowes and Arrowes shot at vs after our sterne: in recompence whereof we discharged sixe Muskets, and killed two or three of them. Then aboue an hundred of them came to a point of Land to shoot at vs. There I shot a Falcon at them, and killed two of them : whereupon the rest fled into the Woods.” From the 1625 edition of Samuel Purchas, Purchas His Pilgrimes, 595. Transcribed by Brea Barthel for the New Netherland Museum, Albany, New York, and its replica ship the Half Moon.In Sapponckanikan (Tobacco Field) (2019), Michelson considers the historic conditions of a location even more specific to the Whitney Museum—the Lenape fishing and planting site called Sapponckanikan, which was at the foot of present-day Gansevoort Street on which the Whitney is sited. Referencing images from his sister’s garden, he collaborated with artist and app developer Steven Fragale on an augmented-reality (AR) installation that virtually fills the lobby of the Museum with a lush circle of the leafy tobacco plants, which are still used ritually in Indigenous communities. The work poignantly subverts the institutional space by digitally remapping it as an Indigenous one, a gesture that reminds visitors and museum staff alike of their presence on unceded Indigenous land. In an interview about Mantle (2018), Michelson’s permanent public monument commissioned by the Virginia Indian Commemorative Commission for the grounds of the Virginia State Capitol in Richmond, he describes one of the underlying tenets of his work: “I was interested in the notion of Indigenous people as hosts, not as victims. Not as acted upon, but rather in terms of what Gerald Vizenor calls ‘survivance’—an active, continuous presence. I wanted to stress, through the work’s form and scale and the use of native materials and plants, this sense of being a host rather than the guests or the wards.”Christopher Green, “In the Studio: Alan Michelson,” Art in America, December 1, 2018.

Gerald Vizenor, the Anishinaabe scholar whom Michelson cites, conceptualizes Native survivance as “an active sense of presence over absence.”Gerald Vizenor, Survivance: Narratives of Native Presence (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), 11. Survivance involves rejecting narratives of victimry and instead drawing on what Vizenor calls natural reason, “by a consciousness and sense of incontestable presence that arises from experiences in the natural world.”Ibid.Michelson demonstrates the practice of survivance in his site-specific works, which point to the layered histories of places to highlight their Native inhabitants and their uses of these sites: “I wanted to activate a history of Indigenous people as hosts of strangers who then decided to stay.”Green, “In the Studio.”This effort parallels Native Hosts, an ongoing series of public-art installations that Cheyenne and Arapaho artist Hock E Aye Vi Edgar Heap of Birds began in 1988. These works pay homage to the Indigenous communities on whose lands settler-colonial cities are built, borrowing the typography and format of road signs to reproduce the settler names for each location spelled backward and that of the “Native Host,” often a local Indigenous village or sacred site, spelled forward. Heap of Birds describes these signs as “punctures” intended to perplex and thereby prompt an investigation of the Native histories of the locations where they appear.“Edgar Heap of Birds,” Pitzer College official website. Accessed October 16, 2019. Sapponckanikan similarly prompts visitors to the Museum to interrogate the history of the Whitney and its environs by superimposing sacred Indigenous plants on its lobby.

Michelson again uses AR to bring suppressed histories into the present in Town Destroyer (2019). Viewed with the naked eye, the work comprises a horizontal strip of wallpaper depicting a section of the front parlor wall of George Washington’s mansion at Mount Vernon, rendered in the contemporaneous style of French scenic wallpaper (which sometimes included stereotypes of Indigenous people in its exotic mise-en-scène). This particular swath eschews such imagery, inserting into the scene a bust of Washington based on the famous one by Jean-Antoine Houdon. Viewed through a downloadable AR app, a virtual, three-dimensional bust emerges from the paper, its surfaces awash with moving maps, portraits, historical markers, and other material related to the brutal Sullivan Expedition against the Haudenosaunee in 1779. Orchestrated by Washington, the campaign resulted in their forced displacement from their homelands in what is now New York State, their towns, homes, crops, and provisions destroyed.Barbara Alice Mann, George Washington’s War on Native America (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009), 67.The sound track alternates drum-and-rattle recordings with the voices of Haudenosaunee community members speaking in various dialects the word Hanödaga:yas—“Town Destroyer,” their name for George Washington. Michelson overlays the ubiquitous portrait of this Founding Father with a corrective truth, using the monument as a screen onto which he projects “a history lesson” on the devastating campaign that led to Indigenous dispossession and paved the way for the settler-colonial development of New York. Town Destroyer evokes a concept articulated by scholar Taiaiake Alfred: “The strongest weapon we have against the power of the state to destroy us at the core is the truth.”Taiaiake Alfred, “Warrior Scholarship: Seeing the University as a Ground of Contention,” in Indigenizing the Academy: Transforming Scholarship and Empowering Communities, ed. Devon A. Mihesuah and Angela Cavender Wilson (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004), 95.

Michelson’s interests in vision and colonial power have led him to frequently repurpose surveillance technologies to question the very system that creates and deploys them. The image-recognition software used in Town Destroyer, for example, represents a recent advancement in surveillance tech. In Wolf Nation, the footage of the red wolves is available because of their being captured on webcams 24-7, a visibility that Michelson appropriates to call attention to their possible extinction and the broader socio-ecological corrosion that is responsible for it. Even the searchlight in Shattemuc is a surveillance technology, and one with an explicitly colonial past, developed in the mid-nineteenth century by European powers and used for military purposes.Henry H. Haferkorn, “Searchlights: A Short, Annotated Bibliography of Their Design and Their Use in Peace and War,” 256. In Professional Memoirs, Corps of Engineers, United States Army, and Engineer Department at Large 8, no. 38 (March–April 1916), 250–63. Published by the Society of American Military Engineers.In Michelson’s hands, its illuminating blast reveals how the land has been transformed today into a commodity to be exploited. Under the unsteady beam of the searchlight, the shoreline, with its various residential and industrial developments, appears vulnerable.

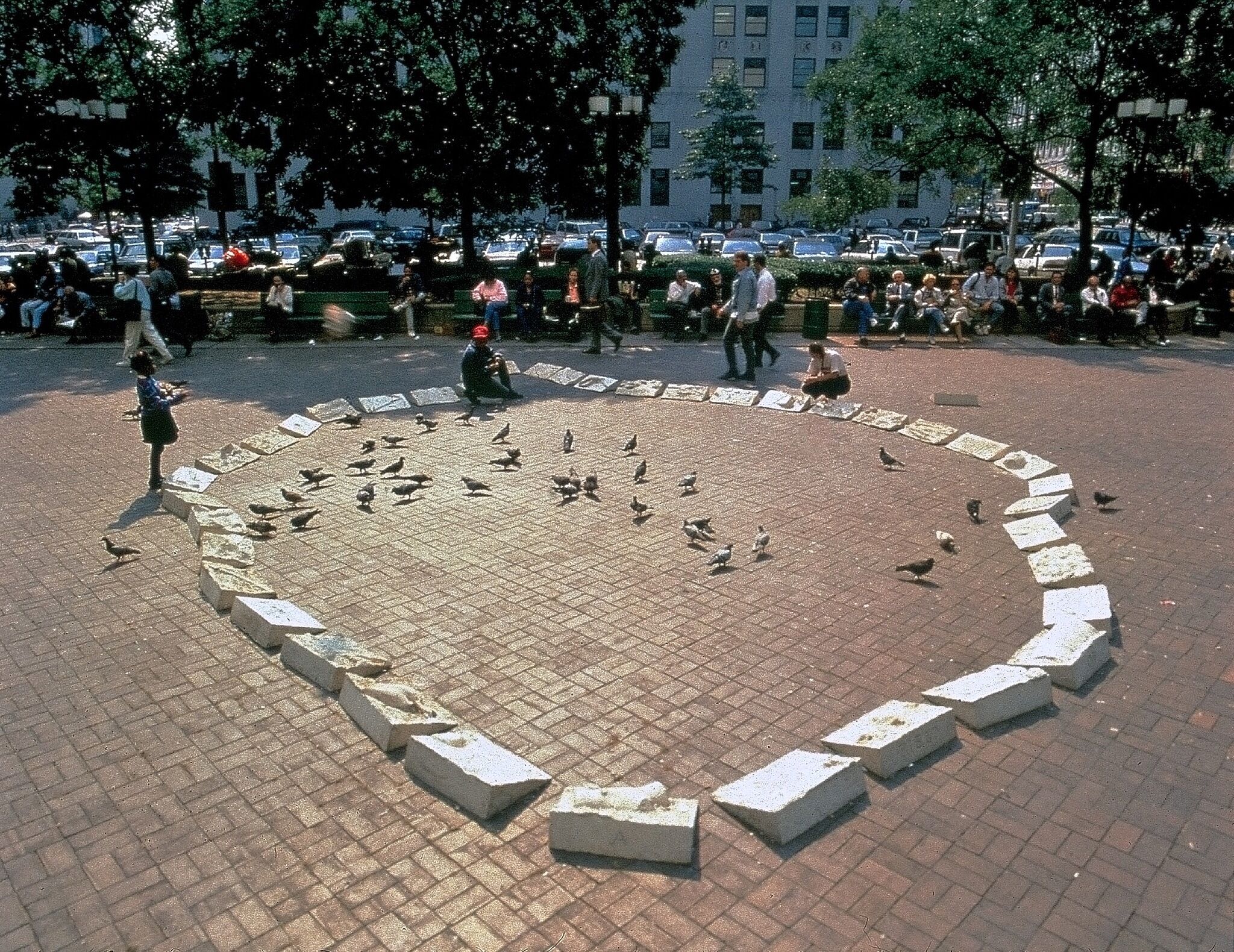

Working in the field of surveillance studies, scholar Simone Browne has examined how the state uses surveillance and coercion mechanisms to specifically target Black and Indigenous communities.Simone Browne, Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), 68.Light itself is a tool of the settler-colonial regime: in the pre–Revolutionary War colonies, so-called lantern laws were one of the government’s tools to regulate the movement of Black and Indigenous people, forcing them to be “constantly illuminated from dusk to dawn, made knowable, locatable, and contained within the city.”Ibid., 79.Those who did not carry candles or lanterns were subject to public lashings. One of Michelson’s early works, Earth’s Eye (1990), uncovers the history of a place closely connected to lantern laws, Collect Pond, which was once a pristine water source in Lower Manhattan. Also known as Fresh Water Pond, the site was explicitly implicated in local lantern laws; the “Law for Regulating Negro & Indian Slaves in the Nighttime” stipulated in 1713, “No Negro or Indian Slave above the age of fourteen years do presume to be or appear in any of the streets on the south side of the fresh water in the night time above one hour after sun sett without a lanthorn and a lighted candle.”Ibid., 78.This “fresh water” is the very pond that Michelson retraces in Earth’s Eye. After the arrival of settlers, Fresh Water Pond was soon polluted by surrounding tanneries, becoming a breeding ground for typhus that was drained in the early nineteenth century.Deborah Everett, “Light on Shadowed Ground: Alan Michelson,” Sculpture Magazine 26, no. 4 (May 2007), 32.In Earth’s Eye, Michelson restored the pond’s former contours, marking its outline with cast-concrete reliefs of plants and animals native to the site and crops grown by Indigenous people local to the area. The result was a kind of monument referencing the site’s social and ecological degradation, an invocation of the pond prior to the arrival of colonizers and their racist laws of social control.

Michelson undermines monumentalized American national myths. In subverting physical monuments, he also takes on the ideological ones: “monuments can tell different stories now than they did before.”Green, “In the Studio.”Toward the end of Town Destroyer, he overlays Washington’s forehead with an image of the 1794 George Washington Belt, a famous six-foot wampum belt on which a house representing the Haudenosaunee (People of the Longhouse) is connected to two figures representing the Mohawk (Keepers of the Eastern Door) and the Seneca (Keepers of the Western Door). The figures hold hands with thirteen others, one for each of the newly formed United States.“George Washington Belt,” Onondaga Nation official website. Accessed October 16, 2019.The belt’s white beaded background symbolizes peace and friendship; it ratified the Canandaigua Treaty, intended to establish peace and demarcate Haudenosaunee lands following the American Revolutionary War and the Sullivan Expedition. Michelson superimposes the Washington bust, an enduring symbol of the settler American political tradition, with the wampum belt, an enduring symbol of the Haudenosaunee one. He thereby casts the bust “into a story that’s very different from the one it was designed to tell.”Green, “In the Studio.”Instead of reinforcing the American nationalist history in which it is usually evoked, the bust becomes a screen onto which the wampum peace treaty is projected, honoring the enduring resonance of the Haudenosaunee worldview. Michelson’s works powerfully complicate dominant narratives with other perspectives, an impulse that is also embedded in the structure of his practice: “I make panoramic works because you can’t just take them all in and think you know what you’re seeing. It forces you to look at things from more than one direction and one angle, and to look at life as flux rather than something that you can fix and control.”Quoted in Kate Morris, “Art on the River: Alan Michelson Highlights Border-Crossing Issues,” American Indian Magazine (Winter 2009), 40.